On 12 May, I had the pleasure of delivering my public lecture on Europe’s role in the shifting landscape of tech rivalry. The lecture was based on the European Research Council-funded CODE project and hosted by the Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

📸 Curious what the CODE kickoff looked like in full swing?

Photos from the evening are just one click or tap away. → Photo Gallery

I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to my CODE team – your support, input, and energy were invaluable. I am also grateful to Pieter Ballon, VUB Vice-Rector of Research, for opening the event so eloquently and setting the scene.

The central theme of the lecture was the technological competition between China and the US, and its implications for Europe.

The first part of the lesson focused on understanding the underlying dynamics of technological competition. To this end, the CODE project has placed a strong emphasis on the concept of innovation ecosystems in the digital age. Over the last year and a half, we have studied how leading digital companies innovate, using a mix of qualitative research and data on patents and market indicators.

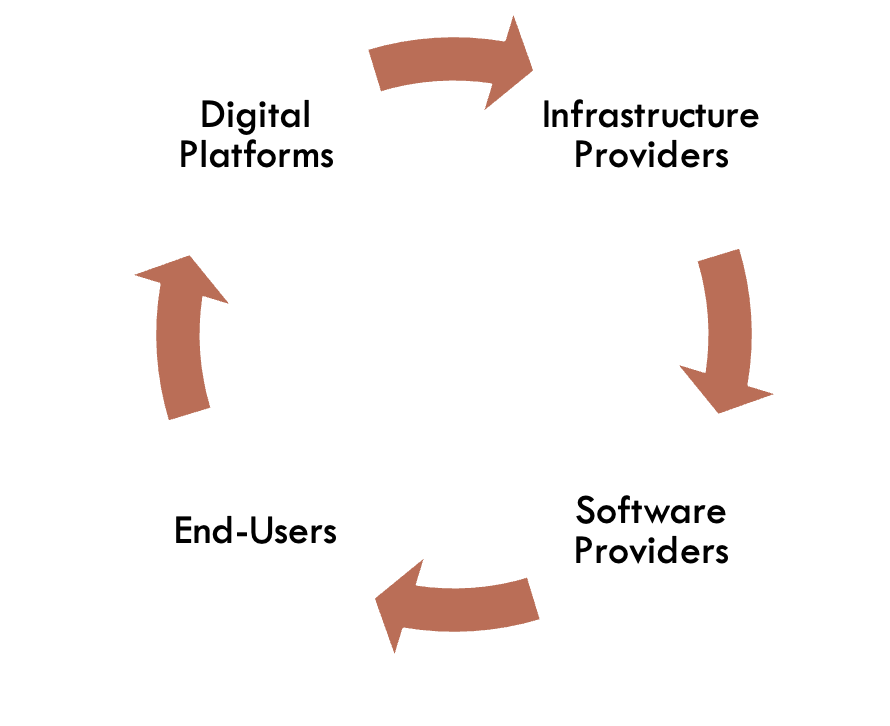

We then observed that, in the digital age, innovation is produced through continuous feedback loops involving four key players: major digital platforms (often based in the US or China), infrastructure providers (including semiconductor manufacturers, cloud computing providers, undersea cable providers and telecoms companies that own most national infrastructure), software providers, and end users. One particularly interesting aspect of the digital age is indeed the close link between production and consumption. Consumers of digital products provide essential feedback that improves the products themselves (think of how we contribute to training LLMs).

This makes the digital innovation ecosystem centralised, with a few large groups competing with each other. Today, digital platforms create and capture value by collaborating with infrastructure providers, open-source software communities and end users to meet their evolving needs. It is also decentralised, depending on widespread innovation from start-ups, open-source communities, and end users. These innovation ecosystems are global in nature, often transcending the boundaries of companies and countries.

To be sure, the digital innovation ecosystem is not fixed but is instead influenced by geopolitical dynamics. What we call technological competition is, in fact, nothing more than different states' desire to manipulate this ecosystem for political gain. They try to improve their own ecosystem while hindering that of their opponents.

In this context, we can understand US export controls on advanced semiconductors and China's export controls on critical raw materials, as well as policies that incentivise companies and consumers to buy domestically.

In the second part of the lecture, we applied the digital innovation ecosystem to Europe in an attempt to understand its position with regard to digital platforms, infrastructure providers, software providers, and end users.

The results of the research will be published in an academic article soon — but when it comes to academic publications, 'soon' is a relative term — and there are three points that should be discussed more in the public debate on Europe and technological competition.

The supply problems in Europe (e.g. in semiconductors or cloud computing) are well known. There is less debate on demand. For example, European companies lag behind when it comes to adopting cloud technology and AI. A lack of demand could easily explain a lack of supply.

Where should we concentrate our resources? Some argue that we should try to focus on all four of these areas of the digital innovation, while others claim that we should invest in areas where we already have a head start or where European companies could become indispensable. This will probably require a sector-specific approach.

Based on CODE preliminary findings, the priority should be to develop innovation ecosystems across Europe. Currently, Europe has clusters based in various areas. The political challenge lies in uniting these clusters while avoiding creating winners and losers within Europe by prioritising some clusters over others. This is an open question, but probably one of the most important ones for the years to come.

We discussed these three points with our audience and received some brilliant insights. In future posts and academic publications, we will expand on the concept of digital innovation ecosystems and explain how they can be used to understand current technological competition and improve Europe's position.